Health outcomes – does anything else matter?

pharmafile | October 27, 2010 | Feature | Research and Development | Les Rose, evidence-based medicine, healthcare outcomes, randomised controlled trials

So the mould of British politics has been broken, and we now have a government with probably a broader range of views than we have ever had before.

A politician once said that your opponents are in the other parties, but your enemies are in your own party – you need only read Alastair Campbell’s recently published diaries to confirm that. Does the coalition mean that armed neutrality between the partners will inevitably turn into warfare?

During the frenzied coalition negotiations, I was struck by the alacrity with which cherished policies were abandoned as the scent of power wafted around the room. As a result, the Liberal Democrats no longer oppose immediate and drastic public spending cuts, and the National Health Service is of course in the firing line.

Before the election, the Conservative Party stated that it would be looking seriously at NHS outcomes, and the Department of Health has issued a consultation which seeks views on which outcomes are considered important.

So far, three main categories are proposed, which are effectiveness, the patient experience, and safety, in that order. Effectiveness is a term that is in danger of being all things to all men, but it is not usually taken to be quite the same as efficacy.

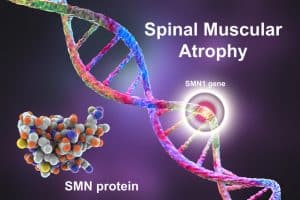

In drug development, we conduct rigorously designed clinical trials firstly to detect, and then to measure efficacy, under controlled conditions. This may or may not reflect the impact on a patient’s daily life.

The value of randomised controlled trials

Hence, randomised controlled trials (RCTs) have recently come under attack. In October 2008 Sir Michael Rawlins, chairman of NICE, famously challenged the ‘gold standard’ position of the RCT, and set out what he saw as its limitations. This was of course seized upon by those with an interest in eroding evidence based medicine, but if you read Rawlins’ Harveian Oration carefully, he was not dismissing the RCT at all. He was simply explaining where RCTs are appropriate and where they are not.

For example, can the results of an RCT be applied to the broad range of clinical practice? Too often the answer is no, so further evidence needs to be obtained from more pragmatic trials. These would typically enrol a population more representative of patients seen by clinicians on a daily basis.

Submissions for marketing authorisation are solidly based on RCT evidence, or in other words, they are assessing efficacy. Of course, they also assess safety, but let’s return to that later. While the design of trials included in a dossier might be actively debated at present (for example adaptive designs, and Baysian statistics), the principle of rigorously controlled conditions seems likely to continue. Basically, the current regulatory process delivers a shopping list of treatments that are eligible for the NHS to use. They have been shown to work, under those research conditions, and up to the end of the last century, NHS purchasers were expected to understand those conditions in order to make therapeutic decisions.

But then we have the problem of generalisability. Modern antidepressants have recently been criticised for having little or no effect over placebo in some important patient groups. Hence the ‘fourth hurdle’ of NICE, intended to enable better decisions by assessing cost-effectiveness. Note that the term is not cost-efficacy. While RCT evidence is included in NICE appraisals, a major component is quality of life – ie. measuring the impact of the treatment on daily life. In concert with pragmatic studies, ‘real world’ studies, and a range of other research approaches, quality of life measures do obtain information on effectiveness as opposed to efficacy. If the government is interested in outcomes, then the field is rich with validated tools, from rigorous RCTs to effectiveness studies in all their various forms.

Could we speed the process by skipping the RCT stage? I see great dangers, mainly of false positives. The RCT can tell us reasonably reliably whether there is anything going on, and effectiveness studies can tell us whether what is going on matters. One type of effectiveness study would be an uncontrolled observational survey. I am not particularly advocating this approach, but such studies do get a lot of media attention. What if we announced positive outcomes from an observational survey, but either had not done any RCTs, or had done RCTs that showed no effect? Would the observational study be worth anything? You decide.

We do RCTs in order to remove as many biasses and confounding factors as we can. Further studies that test generalisability, necessarily include some confounding factors, so can be misleading on their own. They can only stand up alongside RCT evidence. Well that is my view but I do know people who differ from that, and the current consultation will attract some conventional and unconventional views. I hope the minister will have sufficient experts to guide him. The problem is that politicians can be perfidious and illogical. During the election campaign, both coalition partners were asked by a journalist about their policies on science, including health.

The Conservative Party said it would be “wholly irresponsible to spend public money on treatments that have no evidence to support their claims”. The Liberal Democrat policy was very similar. We now have a Conservative secretary of state for health, who has overseen the government’s response to the House of Commons Science and Technology Committee’s report on homeopathy. The government agrees that homeopathy has no evidence of effectiveness, but declines to stop the NHS from funding it.

Of course, homeopathy is a very small cost to the NHS, but there are other areas of established clinical practice that have no good evidence that they work.

Politics and evidence-based medicine

One has to ask to what extent the government really is committed to evidence based outcomes – especially when they have appointed David Tredinnick MP to the select committee on health. He famously charged to his expenses the cost of astrology software, which he thought would be helpful for the application of homeopathy.

The best health outcome for the government would be if we all had productive disease-free working lives, and then died at the point of retirement. For all countries with organised healthcare systems, the greatest worry is the cost of long term care, for chronic diseases and for the elderly. While these present attractive and growing markets for pharmaceutical companies, the ability of the payers to sustain them is a major question. But no government is going to get elected on a platform of elderly euthanasia, so the compromise has to be to extend health into old age, and thus reduce demand. Even better, keep people working into old age, and that is already on the cards. In the current economic climate, paying taxes for longer and calling on healthcare less is a potentially winning formula, but it isn’t going to get the government out of its short term bind. I think they are looking for quicker fixes.

The safety outcome is an interesting one, in that it can’t stand alone – none of them can. What really matters is not safety per se, but the risk:benefit ratio.

We have NICE which assesses effectiveness in relation to cost, but do we have any body which assesses effectiveness in relation to harm? True, there is a lot of publicity about iatrogenic disease, but much of this simply adds up all the mortality and morbidity without considering the positive outcomes.

For the aforementioned homeopathy, the risk:benefit ratio is zero – no effect, and no (direct) harm. RCTs are mostly too small to evaluate safety adequately – after all, they are powered to test efficacy not safety. Post-marketing surveillance generally captures adverse events, and relates these to exposure to treatment, but effectiveness is often overlooked. Do we need large scale observational studies designed specifically to measure effectiveness in relation to safety, and adequately powered to do so? If these are already going on, we don’t hear much about them.

Neither does the consultation mention the transatlantic buzzwords, comparative effectiveness research, now funded by the Obama administration’s Recovery and Reinvestment Act.

Head-to-head studies continue to be something of a gap in the literature, and even when they do appear, are reported to be vulnerable to sponsorship bias. Should the vaunted efforts to build research capacity in the NHS be directed towards independent studies in this neglected area? Sadly the government is wanting to spend less money not more, but maybe this could be funded from an industry levy, as proposed by some.

I must not forget the third outcome in the consultation, the patient experience. Having that hip joint replaced is a desirable outcome if it restores mobility, but it’s not so good if you had to wait a year for it and kept having your operations rescheduled. More relevant to us, treatment that is pleasant and easy to use provides a better patient experience, but this can be hard to separate from the better compliance that comes with it. There is excellent evidence from many studies that improving adherence to treatment not only improves clinical outcomes, but actually saves money for the healthcare providers.

So the overall message seems to be that evidence based outcomes can’t be separated from each other. What will the government do? Well all my previous experience of public consultations is that they are designed to reinforce the decisions which the politicians and bureaucrats have already made. Call me a cynic if you like, I won’t mind, but I prefer to be called a sceptic.

Les Rose is a freelance clinical scientist and medical writer. www.pharmavision-consulting.co.uk

Related Content

Drug development contracts: can lessons be learned from healthcare delivery?

There is a very good question to ask at the beginning of every project: “What …

Medical publishing: can we rely on it?

The explosive proliferation of journals suggests that medical publishing is an attractive business. But it’s …

The numbers game: getting quantitative information to patients

The great physicist Lord Kelvin said: “If you can measure something, and express it in …