RNA interference – still the great white hope?

pharmafile | March 3, 2011 | Feature | Manufacturing and Production, Research and Development | RNA interference, rnai

The emerging field of RNA interference – also known as ‘gene silencing’ – is one of the most promising in medical research today. Some have even predicted the technology could match or surpass the way monoclonal antibodies have revolutionised medicines.

The leaders in the area are now advancing into late-stage trials, but as with any cutting-edge area of medical research, there remain doubts about whether or not technical difficulties of converting RNAi theory into effective medicines can be overcome.

Confidence in the field was dealt a serious blow in November, when Roche announced that it would end its in-house RNAi research, and many other big pharma companies have gone quiet on the area after a period of excitement and investment a few years ago.

So now Roche has dropped out of the race, who remains in the field, and what obstacles must they overcome?

The promise of RNA interference

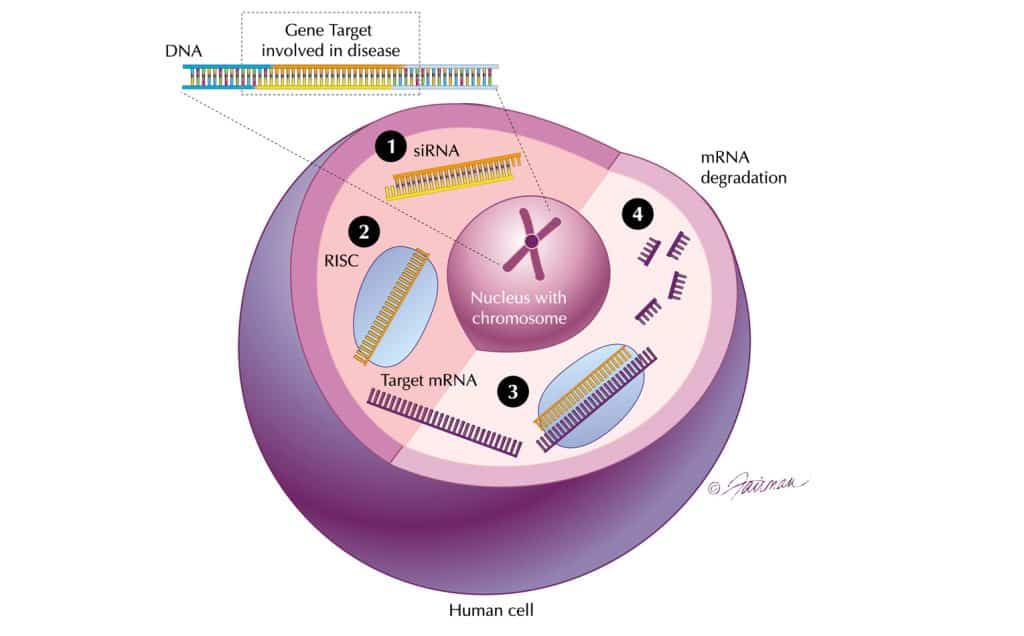

‘Messenger RNA’ plays its messenger role carrying genetic information to the ribosome, where this code is converted into proteins. By blocking the messenger RNA, a disease bearing gene can thus be ‘silenced’ (see box, right, for definitions).

As messenger RNA is involved in all cells, RNAi has the potential to open up the entire human genome to therapeutic intervention, including targets previously considered ‘undruggable’ and inaccessible to small molecule therapeutics.

The technology promises to harness a natural process called RNA interference (RNAi).

RNAi promises to unlock the functional proteomic knowledge from the Human Genome Project. Currently, only around 5,000 of the 25,000 or so human genes have proved to have corresponding successful drug targets – these are the receptors that lie on the cell surface and are therefore accessible.

The RNA sequence to be synthesised must be carefully designed, to ensure it does not hit genes that have similar sequences. A well designed RNA ought to be very specific to its target, thereby reducing the risk of side effects.

Much of the industry’s current expertise resides in a handful of small biotech companies, with two North American companies playing a pivotal role in the advancement of the field – Alnylam, based in Cambridge Massachusetts and Tekmira in British Columbia in Canada. Others in the field include Santaris Pharma (based in Hørsholm, Denmark) and UK-based Silence Therapeutics.

Alnylam expects to have five RNAi therapeutic products for genetically defined diseases in advanced stages of clinical development by the end of 2015.

The field of RNAi is now around ten years old, and different companies have developed different approaches and technologies to harness RNAi.

Most firms have selected ‘short interfering RNA’ (siRNA) as the best route, though some are investigating MicroRNA (MiRNA).

“siRNA is a powerful way of developing new medicines and we want to use it to serve unmet needs,” says Akshay Vaishnaw, VP Clinical Research at Alnylam. “We always go for clear validated targets, where there is a lot of knowledge about their role in pathology, and where there is no existing small molecule therapy, such as our programmes in Huntington’s Disease and respiratory syncytical virus in lung transplant patients.”

Roche’s withdrawal and other setbacks

Roche’s decision to end funding of its RNAi work undoubtedly knocked confidence in the field. The company had set up its own standalone RNAi therapeutics, Roche Kulmbach, which had been conducting research in the field since June 2000. Work being conducted at the company’s research centres in Nutley, NJ and Madison, WI will also cease.

Speaking to BioWorld Today, Roche spokesman Darien Wilson commented: “While there has been some progress in solving the scientific and technical hurdles with RNAi, the hurdles remain, in particular cell specific delivery. Also, the most promising indications where we could achieve successful delivery do not fit with our strategy.”

This followed a similar decision by Novartis to end its work with in Alnylam, forcing the company to cut its staff numbers by 25 per cent.

Meanwhile, there has already been one phase III failure of an RNAi drug. Opko Health stopped development of its drug bevasiranib following a phase III study in wet AMD which suggested that the primary endpoint was unlikely to be reached.

The company says it is looking at alternative ways to develop bevasiranib, including new dosing schedules, combining it with marketed products for AMD, and enhancing delivery with novel siRNA delivery vehicles.

Technical challenges – drug delivery

There are a number of major technical obstacles to converting the theory of siRNA into reality, and these all centre around drug delivery. One of the first problems is designing RNAi drugs which will hit the right targets, and have specificity – silencing the problem genes and not affecting other genes or processes.

Researchers must also develop a system which can stabilise the siRNA molecule and deliver it to the target tissue in sufficient quantity to have a therapeutic effect. RNases are ubiquitous in the body and without some kind of chemical modification, the siRNA will simply be degraded before it can reach its target.

Many different drug delivery technologies have been investigated, and it has required a great deal of pre-clinical work to get the more promising technologies into clinical trials.

Vaishnaw believes that there have been quite a few premature approaches.

“We always take a very careful approach, validating our delivery systems in multiple species. Then we can advance to the clinic with high standards of pharmacology and safety.”

Different delivery approaches may be needed for different tissues and there is certainly not going to be any ‘one size fits all’ in siRNA delivery.

However, there is a large body of knowledge from pre-clinical work, where siRNA has been delivered both locally and systemically to a wide range of tissue and cellular compartments.

Tekmira has developed its own patented drug delivery system, which is being used as the platform by numerous pharma and biotech companies.

Tekmira’s system encapsulates the siRNA molecules in uniform lipid nanoparticles, to allow a stable delivery of the RNAi to the target.

Originally known as ‘stable nucleic acid-lipid particles’ (SNALP) the company has now given it the simpler name of lipid nanoparticles (LNP).

Tekmira has partnerships with Takeda, Bristol-Myers Squibb and Alnylam.Tekmira says its LNP formulations process is robust, scalable and reproducible.

Proof of concept

Confidence is growing in the drug delivery methods, and the focus is now shifting to whether the RNAi mechanism itself works in man. There is reason for optimism, based on a growing number of proof-of-concept trials, but there is much still to be understood about the action of the drugs in humans.

Alnylam recently announced promising phase I data in liver cancer for its compound ALN-VSP.

This is the company’s first systemically delivered siRNA. The ALN-VSP trial is also interesting because of the nature of the siRNA molecule it incorporates.

It is the first ‘dual targeting’ siRNA to reach the clinic – consisting of two siRNA molecules, targeting two genes involved in the growth and survival of cancer cells, namely vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and kinesin spindle protein. There is no reason why the strategy of hitting two targets in one molecule wouldn’t work for other siRNAs and it fits well with the combination therapy approach now being employed increasingly in oncology.

In the phase I trial, involving 19 patients initially, ALN-VSP was well tolerated and dynamic contrast enhanced MRI imaging revealed a decrease in tumour blood flow, which was comparable to that seen with other anti-VEGF drugs.

Alnylam’s lead programme is ALN-RSV01, which is an siRNA directed against respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) nucleocapsid protein.

‘‘Viral targets are notoriously difficult for small molecules, although there have been some success with proteases, and this RSV protein is well understood,” explained Vaishnaw. Proof of concept of ALN-RSV01 in man was established in 2008 when a study showed that the compound has significant anti-viral activity. RSV infection is the most common cause of infant hospitalisation in the US, and responsible for a ten-fold higher death rate than influenza in this group. It also causes significant morbidity and mortality among immunocompromised patients and the elderly.

There is no vaccine for RSV, and ribavirin antiviral therapy is of limited effectiveness.

The siRNA approach could be very helpful in the disease, and the 2008 study was an important milestone. Since then, a further phase II study has been completed with ALN-RSV in lung transplant recipients infected naturally with RSV. The findings revealed improved symptom scores and lung function.

The ALN-RSV programme has also shown the stability and compatibility of the siRNA therapeutic with devices, since delivery involves using a nebulizer.

Alnylam has just begun a phase I study in another condition where the target is well understood. Transthyretin (TTR) is a carrier for thyroid hormones and retinol binding proteins. TTR-mediated amyloidosis is a hereditary condition caused by TTR mutations and leading to accumulation of abnormal amyloid proteins. This orphan disease affects around 50,000 people worldwide and causes significant morbidity and mortality.

Pre-clinical studies of ALN-TTR01, the siRNA therapeutic, have shown that it can cause regression of the amyloid deposits and silence the TTR gene.

Meanwhile, Tekmira’s Apo-B-SNALP programme has delivered the first systemic delivery data with an siRNA therapeutic.

In their phase I study, 23 patients with mild hypercholesterolemia were given increasing doses of the siRNA which targets a protein involved in cholesterol metabolism. Safety data was reassuring and two patients, at the highest dose, showed some evidence of cholesterol lowering.

Silence Therapeutics has developed a different approach to siRNA delivery. Their AtuRNAi is a ‘naked’ molecule suitable for some applications, and is a stabilised siRNA that is resistant to degradation. AtuPlex is a delivery platform which is based upon proprietary lipid components which embed the siRNA into multiple lipid bilayer structures, creating a nanoparticle that can be delivered to a range of tissues.

Silence has been working with Quark since 2004 on AtuRNAi compounds against Quark’s proprietary target RTP801.

One of these compounds, PF 3655, was licensed by Pfizer in 2006. This is now in two separate phase II trials in wet age-related macular degeneration (AMD) and diabetic oedema, respectively.

Pfizer researchers presented pre-clinical data at a recent ophthalmology meeting showing that PR 3655 decreases fluorescein leakage, a known endpoint in wet AMD, which is promising for the clinical trial outcomes. Silence is working on an internal phase I trial with an AtuPlex formulation targeting PKN3, a key regulator of angiogenesis, in solid cancers.

The RNAi pipeline

In the last ten years, a total of 14 RNAi programmes have entered clinical development. (ref Vaishnaw AK et al. Status Report on RNAi Therapeutics Silence: A Journal of RNA Regulation BioMed Central 2010 1:14). Seven involve local or topical delivery to the eye, respiratory tract or the skin. The remaining seven are systemic programmes targeting liver, blood or kidney.

From a safety perspective, it is worth noting that almost 1,500 patients and healthy volunteers have received some form of RNAi therapeutic. There has so far been no unique siRNA related adverse effect, and none of the programmes have been put on clinical hold.

Despite the doubts and many technical hurdles, progress is being made.

It seems like it is not a question of if, but only when the field will produce its first drug on the market. Only after that will it begin to be clear whether or not RNAi drugs will move to centre stage in medicines, or if some technical problems make competing R&D routes more appealing.

“In the next decade or so, it will be very exciting because we have spent a lot of time defining the path of siRNA to the clinic. As these products enter the clinic, people will be opening envelopes from clinical trials on safety and efficacy and we’ll have a lot more data,” said Vaishnaw.

“A lot of human proof of concept will be uncovered at Alynlam, and elsewhere. In the middle of the next decade, there will be late- stage clinical development, which will be terrific. Big pharma will enter this field and their own pipeline will emerge. It will be very exciting to work with these big partners.”

OTHER BIG PHARMA COMPANIES INVESTING IN RNAI

Roche is not the only major pharma company that has invested in RNAi technology:

Novartis signed a deal in August 2010 with siRNA specialist Quark Pharma for its kidney injury drug. Quark Pharma is currently focused on targeting tissue and organ cell death in areas including the eye, ear, lung, spinal cord, brain and kidney. Quark Pharma has granted Novartis an option to obtain the exclusive right to develop and commercialise its siRNA kidney injury drug QP1-1002, a p53 temporary inhibitor.

The drug is in a phase II trial for the prevention of acute kidney injury in patients undergoing cardiac surgery. It is also being explored in delayed graft function (DGF) in kidney transplants patients.

In January 2008, Pfizer acquired Coley, a pioneer in a new class of drug candidates called TLR Therapeutics, which target Toll-like receptors. Three of these receptors TLR3, TLR7, and TLR8, are known to be activated by RNAi, as well as certain other innate immune receptors. Pfizer boldly declared in 2008 that it would file an RNAi drug by the end of 2011, but late last year amended its goal. Pfizer says it still anticipates filing an IND before the end of 2011, but now expects it to be for “an in-house nucleic acid drug” rather than one necessarily based on RNAi.

AstraZeneca established a research collaboration with Silence Therapeutics in 2007 to develop and optimise siRNA molecules.

The companies signed a one-year extension to the collaboration in July 2010.

Silence is working with several AZ units in Sweden, the UK and China, as well as its biologics arm MedImmune in the US, on the development of the siRNA molecules.

There are five therapeutic programmes being developed in the joint work, in addition to projects investigating new delivery approaches for RNA interference.

GSK teamed up with Regulus Therapeutics in April 2008 to discover, develop and market novel microRNA-targeted therapeutics for inflammatory diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis and inflammatory bowel disease. Regulus is a joint venture between Alnylam and Isis Pharmaceuticals.

Merck acquired siRNA specialists Sirna Therapeutics in 2007 for more than $1 billion. Since then, no details of RNAi compounds have emerged, and conference presentations by the company have tended to emphasise the role of RNAi as a tool for target identification and validation, rather than as a therapeutic approach.

Related Content

Alnylam and Roche partner for RNAi therapeutic for treatment of hypertension

Alnylam Pharmaceuticals has announced that it has entered a strategic agreement with Roche for the …

Alnylam cuts workforce by a third

Alnylam will cut 33% of its workforce this year as it looks to focus on …

Sanofi to collaborate with UCSF on diabetes research

The University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) and Sanofi are to launch a new collaboration …