Rare diseases – spinal muscular atrophy

pharmafile | January 30, 2026 | Feature | Medical Communications | gene therapy, medical communications, muscle and motor function, muscle weakness, rare diseases, sma

Spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) is a rare disease characterised by voluntary muscle weakness that can lead to difficulties in activities such as sitting up, walking, swallowing and even breathing. Public interest in the condition recently spiked following singer Jesy Nelson’s announcement that her twins had been diagnosed with SMA, leading to a significant rise in Google searches relating to the condition.

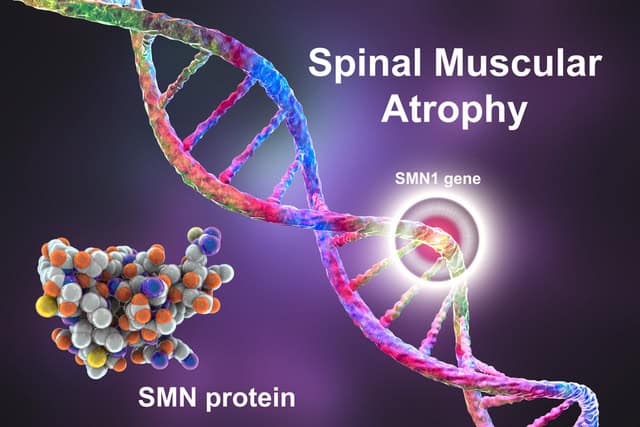

The most common variant of SMA is caused by mutations in a gene called survival motor neuron gene 1 (SMN1). This causes deficiencies in the corresponding SMN protein, a protein that plays an important role in normal muscle and motor function. For SMA cases caused by SMN1 mutation, the most common is related to the deletion of the exon 7 segment.

To develop SMA, a child must have two copies of the mutated SMN1 gene – one from each parent. Very rarely, the mutation can develop spontaneously without either parent being a carrier, but the vast majority of cases are inherited.

If both parents are carriers of the mutated gene, there is a 25% chance that their child will have SMA. There is a 50% chance their child will not have SMA but will be a carrier, and a 25% chance they will neither be a carrier nor have SMA.

There are five main types of SMN protein-deficient SMA, ranging from type 0, which is a very severe form of the disease, typically presenting before birth, that progresses rapidly, to type 4, which appears after the age of 18 and is mild to moderate in severity. The most common form of SMA is type 1, also known as Werdnig-Hoffman disease or infantile-onset SMA. Symptoms of type 1 SMA usually present themselves in the first six months of an infant’s life, and can include trouble with breathing and swallowing.

People with SMA occasionally experience issues with their organs, including the pancreas and heart, and the condition also carries an increased risk of complications from anaesthesia. However, SMA does not affect psychological function or cause learning disabilities.

Typically, the later in life SMA symptoms appear, the less severe the condition. Thus people with type 2 SMA, usually occuring between six and 18 months of age, can sit but not walk without support, and people with type 3, observed after 18 months of age, can walk independently, though not always easily.

Early diagnosis of SMA is crucial to prevent serious outcomes, as by the time symptoms are seen, irreversible damage will have already taken place. The majority of infants with SMA in the UK are diagnosed after symptoms appear, with 60% of them diagnosed with type 1.

UK doctors report that some infants with type 1 SMA are still dying from the condition, and many more are unable to walk and are reliant on ventilators and tube feeding to breathe and eat. By contrast, countries with routine newborn SMA screening – where infants are diagnosed and treated before symptoms appear – have high infant survival rates, with infants having an increased ability to walk.

The NHS currently screen five-day-old infants for nine serious rare diseases using a blood spot test, but SMA is not one of these conditions. In 2018, the National Screening Committee (NSC) decided not to add SMA to the list of conditions that newborn infants are screened for; however, following evidence of the importance of early diagnosis, in 2023 it initiated SMA screening through an In-Service Evaluation (ISE).

However, the evaluation, which must be completed before SMA can be added to the NHS screening roster, has been delayed by a variety of factors.

Currently, there is no cure for SMA, but the condition can be treated and managed through medication, physical therapy and assistive devices. Most medications for SMA, such as Spinraza (nusinersen), Evrysdi (risdiplam) and Zolgensma (onasemnogene abeparvovec), target SMN protein deficiency.

Physical therapy for SMA patients can help to preserve muscle strength and range of movement. Early adoption of a specialised physical therapy programme can slow the progression of muscle shortening, allowing for greater motor function. Additionally, chest physiotherapy and vaccination against respiratory diseases such as flu are important for SMA patients, who are especially vulnerable to breathing problems.

People with SMA also sometimes use medical devices such as walking frames, wheelchairs, braces, splints and orthotics. Spinal surgery can be performed to help stabilise the spine and, in younger children, to allow continued spinal growth.

Alongside newborn screening and improved treatment options, there is also a growing need for an increased public understanding of SMA. There was a significant rise in Google searches for phrases such as ‘what is SMA’ and ‘SMA symptoms’ after Nelson’s disclosure, highlighting a lack of public understanding of SMA and its symptoms.

Sophia Ensor of the Centre for Surgery, said: “When a rare disorder enters mainstream conversation, it often exposes how little the general population knows about its mechanisms, symptoms and available treatments.

“Understanding a disorder like SMA requires reliable, clinically grounded information. Search interest rising by more than 1,000% across multiple SMA-related terms suggests the public is actively seeking clearer explanations about what the condition is, how it is detected and what treatment pathways exist.”

Research into potential treatments for SMA is ongoing. The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS), a branch of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), has ongoing research programmes for SMA in an effort to discover more effective therapies.

NINDS is also undertaking wider research in inherited neurological disorders to better understand how genetic heredity functions.

NINDS scientists are researching cell function in SMA to try to identify cellular processes that could be used as treatment targets. They are also exploring the use of gene editing tools to correct SMN1 gene mutations. By studying the function of the SMN1 gene and SMN protein, scientists hope to learn more about how SMN protein deficiency causes SMA and, consequently, what other types of therapies might be effective.

This article featured in: January/February 2026 – The Pharmafile Brief

Related Content

Digital mental health technologies – a valuable tool in supporting people with depression and anxiety

The potential benefits of digital mental health technology for managing depression, anxiety and stress, together …

Five Facts about spinal muscular atrophy

1 Spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) is a genetic disease involving the loss of motor neurons …

Men’s health – a new report from the Department of Health and Social Care

The UK Department of Health and Social Care has published a new report entitled Men’s …