Neurology comes to the fore

pharmafile | September 7, 2015 | Feature | Manufacturing and Production, Research and Development, Sales and Marketing | Alzheimer's disease, multiple sclerosis, neurology

Neurology is an area where pharma has struggled to deliver in recent years.

Yet the high unmet need for drugs to treat neurological diseases, and the extensive R&D pipelines pharma companies have invested in, have become major drivers of the global neurology drugs market.

Promisingly, the recent increase in research in the fields of Alzheimer’s disease and multiple sclerosis (MS) could finally be yielding innovative new therapies, which experts predict will fuel the growth of the global market for these drugs.

These potential treatments are stimulating public debate about the nature of what the industry, society and patients consider to be meaningful and worthwhile advances in these diseases. MS is the most common neurological condition affecting young adults in the UK, where it is estimated that 100,000 people live with MS. The relapsing remitting form of MS (RRMS) is the most common form, affecting 85% of people.

There are new guidelines and regulatory milestones expected in neurology, with NICE quality standards for multiple sclerosis (MS) due in January 2016, as well as several technology appraisals working their way through the NICE process. Four MS drugs – Novartis’ Gilenya (fingolimod), Teva and Active Biotech’s Nerventra (laquinimod) and Merck Serono’s Movectro (cladribin) are currently listed as ‘under appraisal’ with NICE.

Yet their status in the NICE system serves as an illustration of the problems pharma companies have faced in bringing new MS treatments to market. MS treatment tribulations NICE recommends Gilenya as a treatment for some adults with highly active RRMS, who have had beta interferon treatment for at least a year but who are still having as many or more relapses than the year before, or whose relapses have continued to be severe. It is also being assessed for people with primary progressive MS, which affects 10-15% of people with MS.

However, the appraisals for another two drugs in the NICE system – Nerventra and Movectro – have a far less promising status, as these appraisals have been suspended. Merck Serono withdrew its EMA application for a marketing authorisation for Movectro, after being given a negative opinion for the treatment of RRMS due to concerns about the medicine’s safety. Similarly Nerventra received a negative opinion in January 2014, and again after a re-examination in May 2014, due to poor safety results. Other treatments for the symptoms of MS, including GWPharma’s Nabiximols (sativex), and Fampyra (fampridine), have been rejected as too costly by NICE for the UK NHS.

These cases illustrate the challenges of bringing these drugs to market and demonstrating that they achieve enough benefit to justify their cost to overstretched health systems and payers.

Moving to new outcomes

Some argue that this problem is linked to an over-reliance on conventional measures of efficacy, and that new outcome measures are needed. At the American Academy of Neurology. in April, Novartis presented data that may be a step toward finding new, non-traditional outcome measures with which to assess the efficacy of MS treatments.

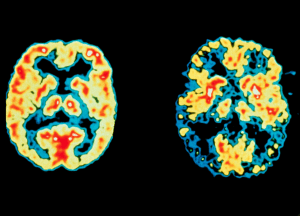

Novartis presented the pooled analyses of two Phase III trials of Gilenya, using alternative methods for researchers to assess the impact of relapsing multiple sclerosis (RMS) on patients. The data suggested that adding brain shrinkage (or brain volume loss) to an existing tool to assess MS disease activity (called m-Rio) will give a more precise prediction of the likelihood of future disability progression, called ‘no evidence of disease (NED) activity’.

Dan Bar Zohar, Gilenya global senior program head at Novartis, says accurate assessment of disease activity is key to guiding treatment decisions in RMS.

“Fifteen years ago, physicians were treating what they could see and what they had under their noses, and the aim was to reduce the number of attacks. Now with the introduction of MRI we have seen that some of the attacks are accompanied by inflammatory brain lesions. They are asymptomatic, however we learnt 10 years ago that some of these lesions become black holes in the brain like Swiss cheese.

“Back then the goals of treatment were different. It was initially with the aim of stopping everything that we can. In the last five years we have learned that relapsing MS patients lose brain volume first. Another important thing is that we are used to thinking of MS as a physical disease but there’s something else beyond the physical symptoms. By looking at a drug’s performance across all four domains of NED activity, doctors can get a more comprehensive view of a patients’ disease and a patient’s response to therapy.”

Need for pharma engagement

The shift from traditional to newer outcomes measures may take some time, Zohar warns, particularly in the often slow world of drug evaluation. “We have made presentations and it is getting traction. Brain volume has been associated with disability progression. It’s a correlation and is also predictive in years zero to two. But these changes take time. In some countries it’s also a matter of reimbursement. More and more countries are including this as part of their health economic assessment.”

The problem will not be solved without more engagement and dialogue between companies and regulators, Zohar says. “Pharma needs to work with regulators, and that’s a totally different discussion. We are willing to have that discussion with regulators, but it is a long process. We are discussing this and raising its importance, and I hope that regulators will consider brain volume loss when assessing MS treatments. Some countries are further ahead than others; in the EU they are familiar with brain volume loss data. They have agreed to look at it, so they recognise it has value.”

The debate around the value of clinical trial outcomes resurfaced after the publication of several new studies at the International Alzheimer’s Association Conference in Washington in July. Lilly, Biogen and Roche all presented studies of their investigational treatments – solanezumab, aducanumab and gantenerumab, respectively.

All three drugs block beta amyloid, a protein which causes the toxic brain plaques considered a hallmark of the progressive brain disease. Alzheimer’s in focus Neurology disease specialist Biogen presented interim results from a Phase IB study of aducanumab. In March it showed it can significantly reduce beta amyloid in the brain and slow impairment in patients with mild disease in a Phase Ib study in 166 patients, and was recently fast-tracked towards a Phase III clinical trial due to promising early results.

The latest aducanumab study tested the safety and effectiveness of the drug at different doses in people in the early stages of Alzheimer’s. The results suggest aducanumab could reduce amyloid plaques in the brain in a dose-dependent manner, and there were early indications that it could also slow declines in memory and thinking.

The results varied according to the dose. The 6mg form of aducanumab failed to reach statistical significance in two key measures, the Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) and the Clinical Dementia Rating scale Sum of Boxes (CDR-SB). The 10mg form performed better on these measures, but concerns remain as it was associated with adverse effects, including brain swelling and the leakage of fluid from the blood in the brain, which was greater at higher doses. And a Phase III trial of Roche’s investigational drug gantenerumab found it was beneficial for markers of Alzheimer’s disease in people with very early signs of the condition, and modestly reduced the levels of amyloid in the brain as well as levels of another hallmark Alzheimer’s protein, called tau, in spinal fluid.

A genuine breakthrough?

The results were mixed, but reported widely as breakthroughs’ in the consumer media – and even earned praise from health secretary Jeremy Hunt, who tweeted: “Exciting news about potential Alzheimer’s drug breakthrough. Massive step forward in quest to find cure or disease-modifying therapy by 2025.”

Yet there is still reason to regard the results from Lilly and others with caution. Dr Margaret McCartney, a GP in Glasgow and a media columnist, wrote: “Placebo-controlled trials of solanezumab did not reach statistical significance on their primary endpoints. However, cognitive scores in a subgroup analysis of people with milder symptoms were purported to show benefit.

“I asked Lilly what the differences were, and the company sent me an interim analysis. It contains graphs that allow comparison of various cognitive instruments over time between the two groups of the extension trial. Never is there a difference of more than two between the groups, and they are scored out of 90 and 56. These are tiny differences: they may mean nothing at all for quality of life, and they may have occurred by chance.”

Dr McCartney is sceptical of the significance of the results and whether they will amount to meaningful clinical steps forward for patients, despite the media clamour. “This is no breakthrough. How did this paper score such extraordinary publicity?” she asks.

Dr Laura Phipps of the charity Alzheimer’s Research UK says: “When developing any new drug, there is always a careful balance to strike between how effective the drug is at treating a disease and whether any drug-related side effects are too severe to allow patients to continue on treatment. “Some drugs have shown promising early effects in people and seem to be able to clear amyloid from the brain. Further trials with these drugs will need to explore how manageable their side effects are for those being treated.”

Overcoming ‘funding fatigue’

But pharma still has a role to play in Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias. The industry is gearing up to support the UK government and research organisations in the quest to revitalise the pipeline for dementia treatments with new drugs that can slow down or stop the progression of the illness.

Pharma giants Lilly, Pfizer, GSK, J&J and Biogen – all big-hitters who featured heavily at the IAAC in Washington – have all signed up to join a $100 million Dementia Discovery Fund to boost research into new treatments, along with the UK government and the charity Alzheimer’s Research UK. This level of investment is needed to overcome what has been labelled as ‘funding fatigue’ within the industry, and the time lag – of over 12 years – since a treatment was last approved for dementia in the UK.

The label came from the Dementia Forum of the World Innovation Summit for Health (WISH), which accused pharma companies of being reluctant to invest in new dementia treatments, as funding fatigue has set in after a ‘history of failures’.

The WISH dementia forum chair Ellis Rubinstein, who is also president and chief executive of the New York Academy of Sciences, says: “Experts speculate that the lack of funding [for dementia research] has created an environment of competition in academia, and that repeated and costly failures in drug development have created funding fatigue in donors and pharmaceutical companies.

“They believe this has caused the field to become more conservative, and has also limited more unconventional strategies and parallel drug discovery opportunities.” The WISH report found big pharma has halved the number of research programmes into new treatments for neurology disorders including dementia between 2009 and 2014. It concluded that “a massive step change in research funding” will be needed to address the medical, economic and social problems that are expected to occur with the projected increase in cases – to 135 million people worldwide by 2050.

An objective answer to the question of whether pharma companies have become ‘fatigued’ by failures in Alzheimer’s disease research can be drawn from industry R&D analysis.

A report by GBI Research suggests that while drug candidates for Alzheimer’s disease have a much higher attrition rate than the industry average – estimated at 95% – the total number of active drugs in the treatment pipeline is relatively large at 583. However, some 77% of the drugs in the Alzheimer’s disease pipeline are in the early stages of development, whereas therapies in Phase III development occupy only 3% of the overall pipeline.

Their analysis of a large number of clinical trials conducted in the Alzheimer’s market since 2006 yielded an extremely high failure rate across all phases of development: 44% for Phase I, 69% for Phase II and 76% for Phase III, with the latter having almost three times the rate of failure compared with the pharmaceutical industry as a whole, highlighting the high stakes for companies in this area of drug development.

“The limits of research knowledge of new avenues for developing treatments for neurological diseases is being countered by technological advances and significant research efforts, with new insights translating into an expanding pool of novel therapeutic targets”, the report concludes.

Pharma often pays lips service to this need, but evidence is growing that more treatments with enhanced benefit-risk ratio for patients could be beginning to emerge from R&D pipelines. Bringing convincing new treatments to market, which have compelling reasons for market access, will be a huge research effort for companies in this area.

Related Content

Esaote presents new MRI system to support brain glioma surgeries

Gliomas are among the most common primary malignant brain tumours

Sanofi completes acquisition of Vigil Neuroscience to early neurology pipeline

Sanofi has announced that it has finalised its acquisition of Vigil Neuroscience, a US-based biotechnology …

Roche receives CE Mark for blood test to help rule out Alzheimer’s

Roche has been granted CE Mark approval for its Elecsys pTau181 test, the first in …