Gene therapy: the tailor-made treatment

pharmafile | June 28, 2006 | Feature | Research and Development | drug development, gene therapy

At the risk of boring my audience, I really can't help beginning with yet another attack of nostalgia ,or rather a wry recollection. You see, the first proper job I ever had was in genetics, when after graduation, I found myself in a public sector laboratory, researching into the genetics of certain bacteria.

A germ of an idea

Back in 1970, we had no basic genetic tools of the kind we have known for a couple of decades or more. We had no restriction enzymes, and genome sequencing was a dream, meaning we could only look at phenotypic effects, particularly nutritional requirements and antigens. All we could do was infer that a particular need for an amino acid or a sugar was related to the absence of a certain gene or set of genes and could see what antibodies the organism engendered on an agar plate. And because of what we knew of coding for proteins by genes (Crick and Watson's 'Central Dogma') a certain amount of information about the genome of the bacterium could be deduced.

All this is astonishingly different from the modern world of, for example, the genome blast sequencing used by Dr Craig Venter's team, who sequenced the human genome in a fraction of the time taken by the massive international project to do the same thing.

I remember how frustrating it seemed at the time, that we could only work by inference and maybe that's what induced me to move into pharmaceuticals. But one thing we did then is still done today. We used viral vectors to transfer genes across the species barrier very unreliably, admittedly, but it sowed some seeds of success for gene therapy.

But back in the 1970s, I was leaving behind my bench research days and learning about prescription drugs. Much the same sense of frustration started to hit me, because I realised that when we did have some idea of how they worked, we were only interacting with biochemical processes, some way down the chain from gene to desired effect.

I thought we needed to get further upstream in the DNA to RNA to amino acid to protein process, and it occurred to me that, as patients' genomes are so variable, it was extremely difficult to predict response.

This was illustrated by some work I did nearly 15 years ago, when I set up some studies in hyperlipidaemia, one of which looked at whether the response to a statin was genetically determined, and I was subsequently delighted to attend the symposium at which the results were presented.

Yes, we found there was a strong genetic component to response, but I was rather less pleased when several delegates said: "So what? We expected that". Now, genetic studies are more commonplace in pivotal clinical trials, although their utility is still hotly debated.

From diagnosis to therapy

We are now seeing genetics migrating from the diagnostic to the therapeutic arena. It is not my place to provide a detailed technical exposition of the field, because I am not an expert, and there are many excellent sources of information on the internet.

In contrast, I want to review the progress being made, and some of the implications for managing product research and development, particularly in human subjects. Possibly the most obvious application of gene therapy is in patients with genetic abnormalities – replacing aberrant or absent genes. Small-scale experiments have been well publicised in the lay media, but I would rather look first at applications which could have a bigger impact on public health.

A good example is traumatic nerve injury. A very frequent result of road accidents, falls, and other forms of violent injury, is the stretching of the spinal cord, which is known as 'avulsion' injury. This commonly involves complete breaks of major nerves, or even of the cord itself, but partial breaks also cause substantial disability. The current treatment paradigm is focused on stabilising the condition, and on preventing any further loss of function until healing can take place.

The outcome is, however, usually very poor. The healthcare burden is considerable, because patients are often young, otherwise fit and healthy, and, hence, have many years of disability ahead of them. In view of the established fact that neurons stop dividing after the nervous system is fully formed, we cannot expect nerve tissue to regenerate by increasing the number of cells. But we do know that there is far more plasticity in the CNS than we previously thought.

There is much evidence for axonal regrowth, and some of the factors which stimulate this have been identified. One avenue being followed with considerable early success is that of the retinoic acid receptor. Retinoic acid is the biologically active derivative of vitamin A, and has been shown to stimulate neurite outgrowth, which should lead to new nerve connections and nerve repair.

Oxford BioMedica's Innurex delivers the RAR_2 gene, which codes for a subtype of the retinoic acid receptor, using a lentivirus vector. It is in late preclinical development, and the most recent data in an animal model of avulsion injury show evidence of new neuronal outgrowth. Oxford BioMedica's LentiVector technology uses a cut down virus as the vehicle and only the components essential for gene delivery are retained in the viral genome.

Cutting edge remedies for modern man's diseases

So, there is the prospect of gene therapy greatly reducing disability in younger patients with injuries, but what about the classic diseases of the developed world? I am thinking of those which are characteristic of an ageing but affluent population (fewer people live long enough in the third world to suffer these diseases). Although classical coronary artery bypass surgery (CABG) is still carried out, ischaemic heart disease is increasingly being treated using less invasive methods, particularly percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty (PTCA).

One problem with this however, as with CABG, is that of further occlusion of vessels after the procedure. Essentially, the atherogenic process which caused the original problem has not gone away (even though it can be slowed down using appropriate drugs such as statins).

As with nerve cells, much has been learned about the factors controlling the growth of the cardiovascular system, and a key molecule is vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). This area is being exploited by GenVec of Maryland, US, whose product BIOBYPASS has entered phase IIb.

The vector in this case is an adenovirus, of the virus family associated with respiratory tract infections, and the product needs to be very carefully placed in the correct area of the myocardium.

GenVec is collaborating with Johnson and Johnson, whose guidance and catheter technology is a key component in the NOVA study, which was launched in February last year. The product has shown very encouraging results so far by stimulating the growth of collateral vessels, to overcome the existing occlusion.

Among the most recent announcements is the exciting prospect of correcting the abnormality underlying Alzheimer's disease. A team at the University of California in San Diego reports encouraging results in six patients who received genetically modified tissue into their brains.

The implanted cells delivered nerve growth factor to cholinergic neurons in the areas affected by the disease. In this technology, the patients provide their own vector, as skin cells are harvested, genetically modified and replicated, and delivered surgically. Studies in non-human primates have shown about a 50% slowing of disease progression, and initial results from this phase I study are consistent with that.

The sponsor, Ceregene, is also developing gene therapy for Parkinson's disease. Although only at the early pre-clinical stage, in vivo studies have indicated a benefit from delivering glial cell line-derived Neurotrophic Factor (GDNF). This is inserted into the nigrostriatal system in an attempt to prevent the degeneration of substantia nigra neurons and the accompanying loss of the neurotransmitter dopamine. This is more conventionally remedied by giving levodopa and/or dopamine agonists, which are all beset with side-effects and limited efficacy over time.

These are only four examples of exciting developments in gene therapy, even though it has yet to make a major clinical impact. There are some 180 companies involved in the field, using far more varied technologies than could be outlined here. For example, vectors are not always needed, and the functions of genes can be modified in vivo without gene transfer.

Risk versus reward

The diversity of the technologies reflects the expansion of the field, from only 44 companies 10 years ago. Despite all this activity, there is to date only one gene therapy product on the worldwide market, a cancer treatment called Gendicine, and, surprisingly, it was launched in China in 2002.

Does this suggest a high-risk, high-return market? Certainly, there are major difficulties to be overcome. In the US, regulatory control has now been tightened up following the death of a gene therapy patient, and there have been reports of leukaemia following the use of retroviral vectors in successful gene therapy for treating adenosine deaminase deficiency.

In addition, I previously confined this discussion to somatic cell gene therapy, but the germ line is also being explored, with major ethical issues. We are now asking ourselves: "What is normal?" and "How far are we prepared to go towards developing the perfect human?".

Nevertheless, this bright new industry is very confident that these problems will be overcome, and two more products are scheduled for launch this year. Perhaps I should not call it a new industry, as it has been around for a long time, but it is only now showing signs of real progress.

It is rather reminiscent of monoclonal antibodies, hailed in the early 1980s as magic bullets for almost every imaginable disease. Where are they now? Some of them are currently making a big impact in difficult-to-treat conditions, such as asthma unresponsive to inhaled corticosteroids, and rheumatoid arthritis in patients who have run out of treatment options.

In for the long haul

Because of cost and limited routes of administration, these drugs are seen largely as last resorts, but it is clear that they represent quantum leaps in therapeutic effectiveness. It seems likely that gene therapy will follow a similar path, for some of the same reasons.

Monoclonal antibodies have some theoretical (and practical) safety issues, and clearly that also applies to gene therapy, given the level of regulation which is considered necessary by governments.

Companies investing in this field will be doing so for the long haul. Product development will have more hurdles to overcome. Treatments such as those described above for degenerative diseases will need very long clinical trials to demonstrate clearly the effect on progression that will differentiate these products from orthodox drugs.

Admittedly, there are study designs which may shorten the process, using disease progression modelling, but regulatory authorities are very conservative and will need to see claims well-supported by solid data. But before we get anywhere near that stage, we have to get studies up and running, and that presents some challenges.

In the UK, there is an additional step in the ethics approval process in the form of the Gene Therapy Advisory Committee (GTAC). Although it varies from one institution to another, generally local research ethics committees require GTAC approval before considering a protocol. Sometimes they will proceed, but hold their approval until hearing from the GTAC.

In addition, the study site will have its own approval process for any studies involving genetic materials. Disposal can be an issue, even to the extent of clinical waste from patients in gene therapy trials. When putting together the project plan, detailed attention needs to be paid to these logistical issues.

As with vaccines, these biological products will need special conditions for transport and storage, requiring yet more detailed planning.

In common with biological response modifiers already on the market, drug delivery is a major consideration. As well as complicating product development, it has implications for long-term business planning.

For example, if you need third party proprietary technology to deliver your product, can you rely on this being available for the full product lifecycle? You will almost certainly need advice from an intellectual property expert. This constraint will also determine to a large extent whether you can scale up the product for wider application, or whether it will be limited to a niche – the less critical the delivery requirements, the easier this will be.

This is not a comprehensive primer just thoughts from an interested, albeit experienced, observer. An internet search engine will deliver a wealth of information if you enter gene therapy companies. It is an area well worth watching.

Related Content

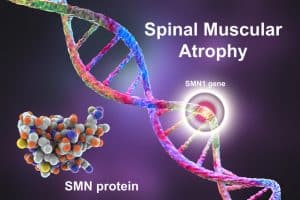

Rare diseases – spinal muscular atrophy

Spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) is a rare disease characterised by voluntary muscle weakness that can …

Five Facts about spinal muscular atrophy

1 Spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) is a genetic disease involving the loss of motor neurons …

Custom Pharmaceuticals launches new company for drug product development

Customs Pharmaceuticals, a full-service contract development and manufacturing organisation (CDMO), has launched Centrix Pharma Solutions, …